The debate about Amazon v the publishing industry is getting so heated and so polarised that quite soon it's going to need its own version of Godwin's law. The passion is almost religious. On the one hand, you have those who say Amazon is a kind of new publishing messiah, casting out the old gatekeepers and ushering in a democratised, consumer-centric book trade. On the other, you have those who see the company as a digital devil destroying all it touches. It's neither. It's just big, strong, and ornery.

Amazon makes money differently from a conventional publisher. It is an infrastructure player. It pays low tax by canny placement – for example, by selling ebooks into the UK from Luxembourg, where VAT is 3.5% instead of 20% – and by having a largely automated warehouse and delivery system, without bricks-and-mortar stores to pay for. It buys in huge bulk for additional savings, and uses its colossal market share to secure concessions from suppliers. It's the Tesco of the book trade, and of course sells much more than books.

It's perfectly true that Amazon's approach is, for the moment, mostly cheaper for the consumer than the now-endangered agency model favoured by publishers. But the agency model's chief advantage to publishers is that it curtails Amazon's control of the market. As a matter of practicality, they wouldn't have had to collude to adopt it: the situation was plain to a blind hedgehog (which, alas, is not to say that they did not).

Before agency was introduced, Amazon boasted of controlling 90% of the ebook market. Barnes & Noble's Nook now has a share in the mid-20s, with Apple down around perhaps half that and assorted others making up a few more percentage points. Whatever agency's sins may be, it opened the way for something like competition, which is why it seems on the face of it painfully odd that publishers should face legal action for anti-competitive practices in adopting it.

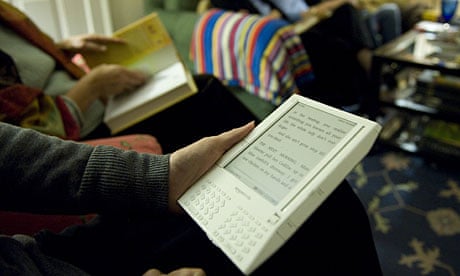

And why is competition important? Because it drives not just lower prices, but better products. And let's face it, the products we have are ho-hum. E-readers are uninspired. They're slabs of plastic with fiddly controls and display a badly-formatted, typographically impoverished rendering of a paper book. That's not the electronic book I want. I want a gorgeous physical object, with paper pages, that can transform into any story I choose, perfectly presented on the page. I want a device from a fairytale, not a bargain bucket. Although, sure, I'd like it to be affordable, too. And that will not happen if one company controls the market. Why should it?

Digitisation was supposed to lead to a great democratisation of access to creative work. The putative business model of the internet age is the garage band, the plucky underdog cottage business that can, by canny use of information technology, compete with the big boys and win. What we're getting is the opposite, a great centralisation of access and, ultimately, control. It turns out that if you want to sell your garage-made product these days, you need a watering hole, a place with many visitors who may want what you're selling, because the hardest enemy is obscurity. Amid the babble of new voices, distinctive ones can be missed even by those looking for them.

So Amazon, Google and Apple are gatekeepers. They have realised that the key to profitability is not investing in risky startups, but owning the marketplace where those startups stand and (mostly) fall. So for the rest of us, outside the walls, what's the point of taking sides in a battle between "legacy" gatekeepers and new ones? Hail the new boss, same as the old boss.

Amazon is a corporation, not a philanthropic trust dedicated to the production of works of art and literature. Some – such as Barry Eisler – see the company as too dedicated to its customers to take advantage of a monopoly to gouge them on prices. I don't agree. Either Amazon sees a direct profit in the future, or it is already turning an acceptable profit by using books as a loss leader to draw consumers to the site to buy garden furniture. We – those who buy from the company – are not Amazon's friends, any more than we are Nestlé's or BP's. We should expect no favours.

If Amazon was truly consumer-centric, it would do away with DRM and adopt the ePub format, allowing users to consume their media on any device and through any software they choose, securing them from obsolescence and errors in DRM servers, accidental deletions and the rest. And that it most emphatically does not do.

The most thunderous argument in Amazon's favour is that the market has spoken, and demands cheaper product. This one I find utterly bizarre. We know very well, in this post-crash age, that the market can be an idiot. The market wanted easy credit extended to all, low taxes and plenty of public spending. The end result was a financial catastrophe that has just plunged us into a double-dip recession and shows no sign of being played out. Sometimes, things cost more than we want. That is a truth we were encouraged to forget in the 90s, but it's one we're going to have to remember. Of course the market wants things to be cheaper. I want a Tesla electric sports car for a tenner, but I don't imagine that will happen either.

Traditional publishing is far from blameless. It has been slow and unimaginative. That is changing, at last, and the effect of the department of justice anti-trust action may ironically be to inspire a serious shift in how the big houses see the electronic marketplace. I hope so. Because if I'm going to get my magic ebook, we're going to need innovation, not locked-in stagnation.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion